Happy Birthday, Peg Leg Bates – Born October 11, 1907

Clayton (Peg Leg) Bates (October 11, 1907 – December 6, 1998), a below-knee amputee from the age of 12, Bates grew up disabled and Black in the Jim Crow South. As a teenager in the 1920s, latched onto the vaudeville circuit, he moved onto minstrel shows and then carnivals, and later joining the Theater Owners Booking Association, which booked entertainers for African-American theaters in the US. Bates performed solidly through 1989 in a career that included vaudeville and clubs, stage musicals, performed on The Ed Sullivan Show 22 times, had two command performances before the King and Queen of the United Kingdom, and eventually taking his place alongside the greatest hoofers in the Golden Age of Dance. Why has Hollywood not made a biopic of this man yet?

He started dancing when he was 5. He danced for coins on local street corners and at age 12 took a farm job, but within days his leg was mangled in a cotton gin accident. With no hospital nearby for black people, his leg was amputated on the table in his mother’s kitchen.

From Rusty E. Frank in an interview for Ms. Frank’s 1990 book ”Tap!”:

He had been dancing for his own pleasure from the age of 5, ”before I even knew I was tap dancing. After losing the leg, for some unknown reason, I still wanted to dance. ‘At first, I was walking around on crutches, and I started making musical rhythm with them’.”

He began dancing again after his uncle whittled him a wooden leg.

”See, I did not realize the importance of losing a leg,” he recalled. ”I thought it was just like stubbing my toe and knocking off a toenail that was going to grow back.”

Click the image below to watch!

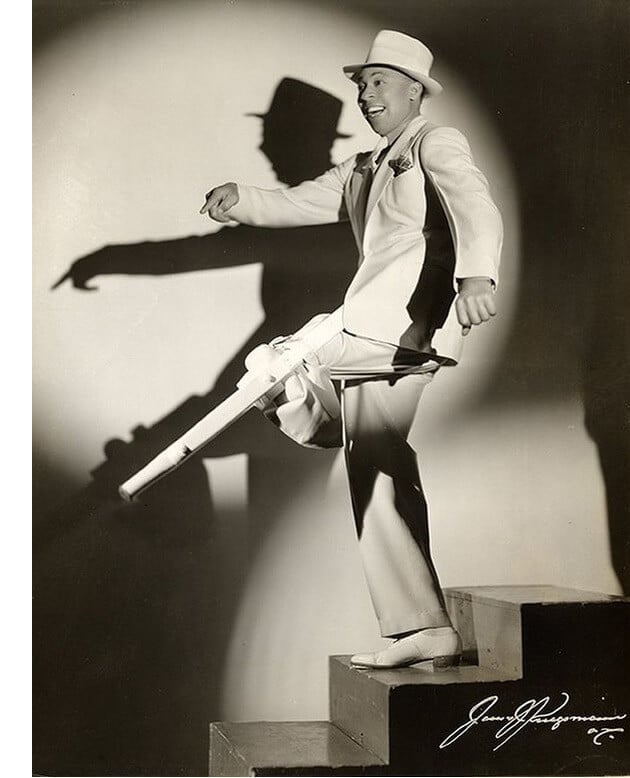

Unlike many tap dancers, Mr. Bates did not specialize in any one genre. “Hard-working as well as ubiquitous, he mastered a variety of styles and pyrotechnical flourishes, reinventing everything for a wooden leg whose half-rubber, half-leather tip gave Mr. Bates’s tapping an unusually deep and resonant sound.

”Well, I’m into rhythm and I’m into novelty,” he told Ms. Frank. ”I’m into doing things that it looks almost impossible to do.” One reason he had mastered so many styles, he said, was to surpass two-legged dancers, adding that he often did. (source)

Here’s what Living with Amplitude had to say about him:

Equally revered by audiences and fellow entertainers, he shared the stage with icons such as Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Fred Astaire, and Gene Kelly. Half a century later, Bates was still kicking it with performers of Gregory Hines’ generation.

“He was reaching for things and trying things and pushing himself,” said Gregory Hines in The Dancing Man, a 1991 PBS documentary about Bates.

“He was accomplishing things so he would be respected on the same level of somebody like Bunny Briggs or Teddy Hale. And he was. Tap dancers were trying to do the rhythms that Peg Leg was doing. He would use that peg in a way that drummers were doing, and [other dancers] were trying to hear it and make it work with their feet. He was expressing himself in a way that other tap dancers couldn’t.”

Here’s the New Yorker describing a Bates performance at a USO show during World War II:

“We saw Peg-Leg when he was finishing an engagement at the Capitol [Theatre] the other day and preparing to go on tour. One of the things he had been doing five times daily was imitating a dive bomber. He’d do this by jumping five and a half feet into the air, turning completely around, and making a one-point landing on his peg leg. Then, still on the peg, he’d back into the wings while flapping his arms.”

Rather than restrict him, the peg leg amplified the quality of Bate’s dancing by offering a tone. Living with his leg also gave him the resolve to continue his dreams as a dancer instead of giving up. “I didn’t want nobody’s sympathy,” Bates said in The Dancing Man. “I wanted to dance on this peg, and I wanted to do some steps on this peg that even two-legged dancers can’t do. And I didn’t let anything stop me.”

Bates made it after being spotted by Lew Leslie, a Broadway producer who added him to the lineup of Blackbirds of 1928 (a hit musical revue). Not only was Blackbirds of 1928 a major hit, but it was also one of the first popular Broadway shows to feature an all-Black cast. The massive success catapulted him into New York’s theaters and nightclubs and lead to him touring Europe and Australia. Bates was also notably the second Black performer to dance at Radio City Music Hall, and he appeared alongside band legends such as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Jimmy Dorsey, and Cab Calloway

Ed Sullivan Appearance, early 1950s

Doing the Shim Sham – With Charles Cook and Earnest Brown, c. 1980s

Bates died on December 8, 1998 at the age of 91 in Fountain Inn, South Carolina where he was born. After his death, his hometown erected a life-size memorial statue in his memory at Fountain Inn City Hall.

.

.

.