Any true fan of Charleston or early jazz music (and movement) should be familiar with the Jenkins Orphanage Band. Whether this is news to you, or you only have heard of them in passing, this article is meant for you! This is a story of a band that helped shape the future of hundreds of Black children that grew up without a family.

The Jenkins Orphanage Band was based in Charleston, South Carolina and was an extremely popular and influential band in the early 1900s. It was made up of orphaned, black children who were a part of Jenkin’s Orphanage.

You might be asking yourself, “What does a band from an orphanage have to do with jazz music and jazz dance history?” Well, let me give you three main reasons why you should definitely learn about the history of this band:

The Jenkins Orphanage was established in 1891 by Rev. Daniel Joseph Jenkins, in the city of Charleston, North Carolina.

Jenkins was a businessman and Baptist minister who one day encountered four abandoned children on the street and decided to take them home. He had been born into enslavement and had been orphaned at a very young age, and deeply related to the abandonment the children felt.

“Although Jenkins had children of his own already – and precious little money with which to take care of them – he nonetheless took the four orphans home to his wife, Lena, and gave them food and beds. This simple act of charity would turn out to be the advent of an enterprise with far-reaching achievements: It would export Southern jazz to the rest of the world, incubate the talents of some famous African American musicians, and even create a new dance step that would come to define the “Roaring Twenties”. [1]

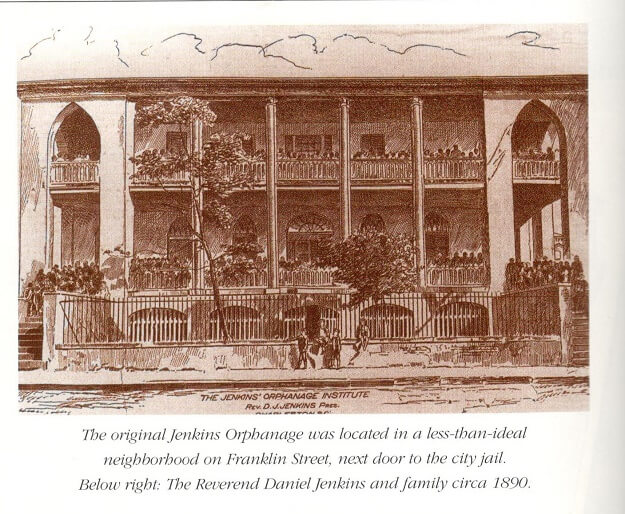

This encounter moved him to quickly take action and start an orphanage for African American children, something that didn’t exist in Charleston at that time. He made a passionate speech before the Charleston City Council which managed to allow him to use an old abandoned warehouse, next to the city’s prison, as home for his Orphanage.

With a small stipend of $100, the Jenkins Orphanage was born.

The original site of the orphanage was on 660 King Street. In 1893, the orphanage moved to the Old Marine Hospital at 20 Franklin Street, which served as the home of the orphanage until 1937, when a big fire consumed the building. Today, the orphanage changed its name to Jenkins Institute for Children and is located in North Charleston, South Carolina.

The orphanage was a success from its very beginning. In its first year, over 360 boys ages 5 to18, had settled into their new home. The location, next to the prison, was not very ideal, as sometimes the noises and screams of the inmates would keep them awake. Nonetheless, the proximity to the prison served as a reminder for the children to respect Jenkin’s strict and moral instruction.

“Jenkins was a strict disciplinarian, reinforcing in his charges the virtues of hard work and responsibility. Most of all, however, he wanted the orphans to be self-sufficient, to be able to grow their own food and to feed and clothe themselves and not be at the mercy of the charity of others.” [2]

Wow. I don’t know about you, but when I read about this, I got the chills.

The fact that a former enslaved individual, in 1891, was able to create something of this magnitude with so few resources completely blows my mind. He took it as his life’s purpose to help provide a better life and better opportunities for hundreds of Black orphans in his city. In the 40+years that Jenkins was running the orphanage, less than ten of the children ended up in prison.

“The orphanage served more than ‘just a place to sleep and [to receive] a hot meal’ for these children; it served as a welcoming home. Children were set for success in their lives, which was very important for African American children as they faced an uphill battle of systemic racism and prejudice.” [3]

The orphanage needed funds to maintain itself and to help Jenkins buy a property to use as a farm to teach the children how to grow their own food. He had petitioned the city for money, but his requests were denied. In addition to that, his attempts to ask for donations from the general public also produced few results, so, the Reverend decided to put together a brass band with the children to raise funds for his institution through performances and touring.

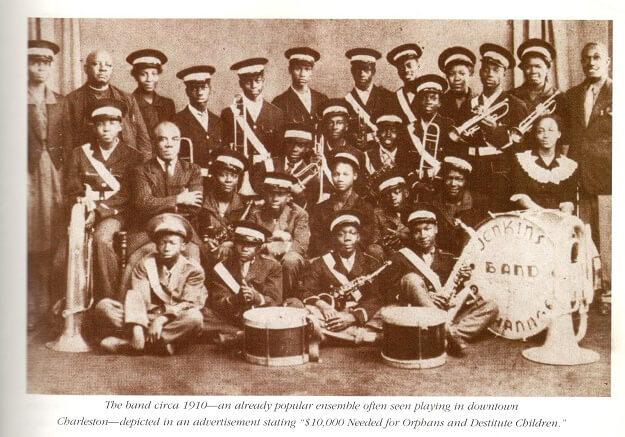

He called for donations of musical instruments, which proved to be much more successful than the call for money, and hired two local musicians to teach the boys: P. M. “Hatsie” Logan and Francis Eugene Mikell. Jenkins himself was not a musician and had never had any musical training. The orphanage’s children were taught how to read music and became proficient at playing all the band’s instruments, which at the time were coronets, trumpets, trombones, tubas, clarinets, bells, triangles and drums. Upon its establishment, it became the only black instrumental group organized in South Carolina.

“His idea was likely inspired by several factors. For starters, Booker T. Washington (the South’s preeminent black educator of the time) had achieved great success using choral performances to garner publicity and donations for the Tuskegee Institute. Teaching the children to play instruments also gave them viable skills, as did their other lessons in such subjects as baking, butchering, farming, and printing. Finally, as Time magazine explained in 1935, “Having on his hands a number of undernourished, rickety and tuberculous youngsters, Jenkins optimistically decided ‘My children’s lungs would get strong by blowing wind instruments.'” [4]

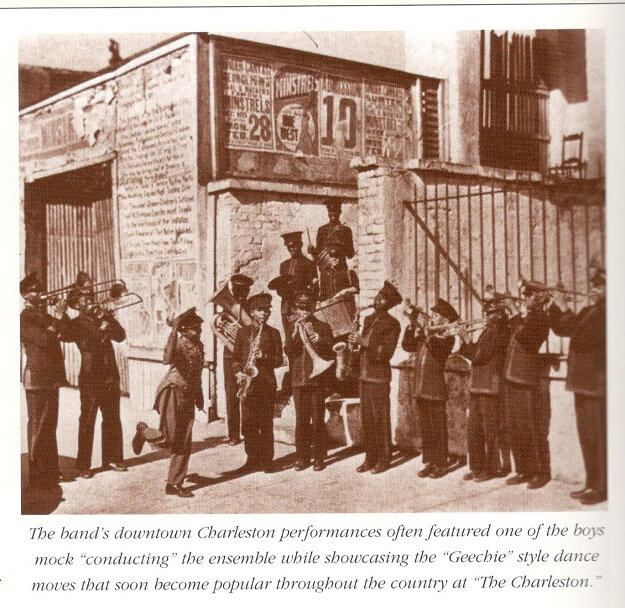

When the group was good enough to perform, Jenkins started organizing concerts in the streets of Charleston, “where they gave bright, natural, highly energetic performances, like electrical currents crisscrossing the air” [1] wearing discarded Citadel uniforms. At the end of each performance, Jenkins would walk amongst the crowd offering his hat for donations, and he would usually collect enough to feed the children for a week.

At first, Jenkins was not very successful raising money in Charleston, so he decided to take the band up to New York city, thinking that the Northern audience would be more susceptible to the African American music of the South; there, they played on the streets and were not able to book a theater, but instead of heading back South as would be expected, Jenkins decided to head to London with the thirteen boys in the band and try his luck there.

London also proved to be a difficult place to land a theater to perform, so they mostly held concerts on the streets as they had before. However, their performances were so scandalous and caught so much attention that the group ended up being arrested for creating public disturbance and, ironically, this is how they started getting some attention.

“Reports of the arrest of this unusual American musical group were recounted in The London Times and soon several local churches came to their aid. After playing to packed crowds at meeting houses in and around London, Jenkins soon raised money for their return home and more. From their escapes in England, they returned to Charleston not only with funding, but with something of an international reputation. Back home in Charleston, the Charleston News and Courier had followed the progress of its citizens with great interest, reprinting the Times reports in full. Shortly after their return, Jenkins purchased a small plot of land outside of Charleston and established the orphanage farm.” [2]

By 1896, the Jenkins Orphanage Band had a pretty vast touring schedule that took them frequently to New York and other East Coast cities in the Summer, and Florida in the Winter. In 1902, they played at the Buffalo Expo, in 1904 they had their own stage at the St. Louis World’s Fair, and soon after they played at the Hippodrome in London. Their main benefactors, however, continued to be churches in both London and Harlem, in New York. By 1905, the band had developed frequent East Coast and European tours that took them to Paris, Berlin and Rome. Some of the biggest honours they received as a band was the invitation to play at the inaugural parades of President Roosevelt, in 1905, and again of President Taft, in 1909.

Travelling around the United States with a black group of artists – children or not – was a big challenge. “Although they rarely stayed in any city for very long, finding sleeping arrangements in Jim Crow-era America was sometimes a problem. But when hotels turned them away, local churches usually put the children up.” [1]

After all the trouble Jenkins and the orphans had gone through to finally be able to book concerts for the band, can you imagine having a hard time booking a hotel for the group to spend the night due to segregation laws? Good thing they had the churches as a back up plan to host them when the rest of the city wouldn’t. Nonetheless, that wasn’t the only racist incident that they had to face.

“Newspapers dubbed Jenkins’ musicians “the Pickaninny Band,” a condescending way of referring to black children. Jenkins understood the insult, but he allowed it anyway because he knew that sort of name was probably good for donations from white audiences.” [1]

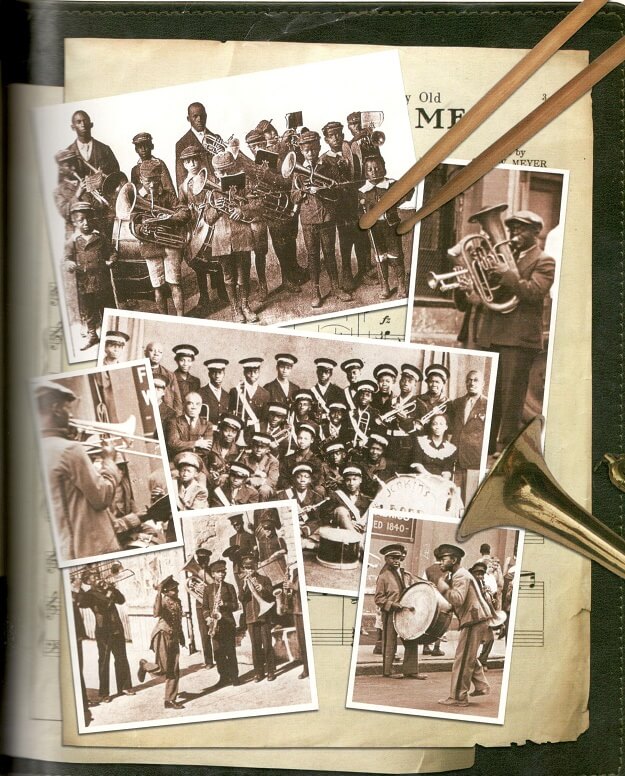

By 1907, Jenkins Orphanage Band had grown to thirty members and was touring far out into the United States. As they became more famous, children in other orphanages, and even some who weren’t even orphans, would travel to Charleston hoping to get a place in the band. By 1913, there was so much demand that Jenkins decided to create a second band. The orphanage had grown to support eight full time teachers, two of which were for music lessons only.

In 1914, the Jenkins band was invited to attend the Anglo-American Expo in London. Apparently, their participation in the event was so highly regarded, that the organizers not only paid for their passage, but also provided money for sleek new uniforms. They received their own pavilion at the event and undertook a rigorous performing schedule from morning till late evening.

While their success outside of Charleston had been growing tremendously, the band continued to perform at its home and had a special relationship with the city.

“The band developed several rituals that endeared them to their white neighbors back in Charleston. One was to stop their bus two or three blocks away from the orphanage when returning from a road trip and to march in the rest of the way, triumphant, while lines of white children followed them, puppy – like and adoring. Another was to go to white neighborhoods on Christmas Eve and serenade the residence from beneath their windows. Local children used to anticipate the advent of the orphanage band on Christmas Eve as much as they did the appearance of Santa Claus. For their parents, a visit from the band constituted a kind of ironic social horror. Sons and daughters were known to have begged their parents to put them in the orphanage so that they could be traveling musicians, too.” [1]

Well, that was certainly unexpected and a little bit disturbing.

The Jenkins Orphanage Band’s fame and reputation would grow year by year and by the 1920s, the orphanage had grown to host five different bands that would go out on tour.

Don’t you wish you could watch them perform? Well, guess what? You can! Thanks to a 1928 Fox Movietone News newsreel feature about the band. In the recording, we get to watch and listen to ten minutes of the band in action performing in the streets of Charleston. Check it out!

And, if you enjoyed that, you can also watch the following clip, from 1926, where you get to see the Jenkins band in action (though not with original audio) playing for the famous Charleston dancer Bea Jackson in front of the orphanage.

Have you ever heard of the famous 1920’s opera Porgy and Bess? If not, then does the song Summertime ring a bell to you? Well, that iconic tune, mostly known in the voices of Ella Fitzgerald or Billie Holliday, was written for this opera in 1929. It so happens that the story of Porgy and Bess was based on a 1925 novel set in Charleston’s African American and Gullah communities and written by Debose Heyward named Porgy. It became an instant best seller.

“The importance of the Jenkins Orphanage Brass Band to the unique cultural heritage of Charleston was also made known by a famous novel that was written at virtually the same time… In its pages the Jenkins Orphanage Band is described as one of the distinctive sights and sounds of Charleston’s colorfully complex black community.” (Symposia)

That is, the band was so deeply rooted in Charleston’s cultural and musical scene, that it became an essential part of the setting of the city.

Before George Gershwin’s musical adaptation of the novel, Heyward himself adapted it into a popular stage play on Broadway. He insisted that the whole cast had to be African American – which was a novelty for Broadway at the time– , imported the dialect of black Charlestonian to the stage and insisted on importing the music itself.

Can you guess which band was invited to perform nightly at the show in New York?

“From 1927 until the show closed to tour in 1928, the number one Jenkins Orphanage Band played every night in the stage performance of the play. Many of the players remember the New York episode as one of the most exciting times in the band’s history. The Broadway run was also one of the most fruitful episodes monetarily speaking in the charity’s history.” [2]

At the beginning, the Jenkins Orphanage Band took inspiration from mainly two sources: military bands and brass bands that played at minstrel shows. Their early repertoire was certainly formed by both of these styles. As time went by and new African American music styles were being developed, the band adapted their sound and included the new rhythms into their repertoire. They would play military marches, Souza marches, Cakewalks, folk tunes and popular tunes.

When the new musical sensation of Ragtime started to get noticed, the band immediately incorporated that new “hot” style of playing into their performances. They were some of the greatest promoters of this music style – as would happen again later with the Charleston – and many reviews of the time mentioned their remarkable ability in “ragging”.

The band was also unquestionably influenced by the Gullah/Geechie culture from the Sea Islands, an intermixed community that developed its own culture and language (a mix of English and many African dialects) during the slave trade, and that still exists today. Their music also reflected a mixture of African, Caribbean and western influences, creating a unique rhythm that became popular in the city of Charleston and was, of course, adopted by the Jenkins band.

“Starting in the early 1920s, observers noted that the band often played a number of “geechie” tunes… As in the Gullah culture, music was not separated from the dance it accompanied, which is no doubt why most accounts also describe the orphanage band performances of geechie music being “conducted” in front by a young boy dancing “geechie” steps.” [2]

Yes, the band helped to spread and popularize not only the music of the Gullah culture, but also its dance steps! And we will get a deeper look into that in a minute, but first…

After the invention of Ragtime, the new jazz and Charleston sounds started spreading in the South and were picked up by the band as well. Because of their intense touring schedule, the band was essential in bringing these Southern rhythms to the North and to the rest of the country – we need to remember that in the 1920s the record industry was just starting out, and the main way to listen and discover new music was still through live performances.

“It was the various Jenkins bands that spread this “Charleston Sound” up and down the Eastern Seaboard. In those early years, when musical innovations were still conveyed through live performances rather than records and airwaves, Charleston’s young troubadours weren’t just earning their keep – they were contributing directly to the budding American jazz scene.” [4]

Yep, that is no small contribution.

As already mentioned above, following the tradition of the Gullah/Geechie culture, the Jenkins band did not separate music and dance. All their performances included some of the members doing geechie steps in front of the band while pretending to be conducting. Many researchers believe they were largely responsible for spreading these steps around the country as they toured and, rumor has it, they might have been the first to come up with the Charleston step itself, which soon became the biggest sensation all around the United States and the world.

There are a few different stories of how and by whom the Charleston step was invented, but one of them gives credit to the boys of the Jenkins band. Here’s what great jazz pianist Willie “the Lion” Smith has to say about it:

“One musician [from the Jenkins Orphanage Band], Russell Brown, used to do a strange little dance step and the people of Harlem used to shout out to him as he passed by “Hey, Charleston, do your Geechie dance.” [5]

So, that is where the name of the dance comes from (mindblown?)! Since those who started doing the step were from the city of Charleston, people started calling the step Charleston, because that was the way they danced there. James P. Johnson, another famous jazz pianist and composer of the famous tune “Charleston” also shared his story about how he came to know the dance.

‘The people who came to The Jungles Casino were mostly from around Charleston, South Carolina, and other places in the South… They picked their partners with care to show off their best steps and put sets, cotillions, and cakewalks that would give them a chance to get off. The Charleston, which became a popular dance step on its own, was just a regular cotillion step without a name. It had many variations—all danced to the rhythm that everyone knows now. One regular at the Casino, named Dan White, was the best dancer in the crowd and he introduced the Charleston step as we know it. But there were dozens of other steps used, too. It was while playing for these southern dancers that I composed a number of Charlestons—eight in all—all with the damn rhythm. One of these later became my famous “Charleston” when it hit Broadway.” [5]

The Charleston became a huge music and dance phenomenon that soon swept the whole nation, in both black and white communities. The Jenkins Orphanage Band was an essential if not the main responsible group for starting and spreading this phenomenon across the country, and that is one of the most impressive parts of the group’s contribution to American culture.

During its decades of activity, the Jenkins Orphanage Band raised and created some incredible musicians. Many of the children went on to pursue a career as professional musicians, and some of them became very successful.

“Jabbo” Smith, who got his nickname in the orphanage after an Indian chief in a Western movie, joined the band in 1915 and soon became one of the group’s preeminent trumpeters. He went on to play at Small’s Paradise in Harlem, New York, and later joined Duke Ellington’s orchestra during the 1920s and 30s. Other two great trumpeters that started their career as part of the Jenkins band were William “Cat” Anderson and Sylvester Briscoe. The first became a well regarded trumpeter in New York and midwest dance bands, and the later joined Benny Moten’s orchestra as one of the lead trumpets.

Even children who weren’t orphans got the opportunity to be part of the band – if they proved to be talented enough – and were able to find in Jenkins band an opportunity to develop themselves as professional musicians. This was the case of Freddy Green.

“Freddie Green, who would later become the guitarist for Count Basie’s Orchestra, also got his start in the Jenkins Orphanage Band in the 20s. Green, who wasn’t even an orphan, was never actually a ward in Reverend Jenkins orphanage. But his case is testimony of how important a force the Jenkins Orphanage Boys Band had become in supporting the creation of early jazz, and how instrumental a role southern musical institutions, especially non-professional ones like the orphanage band, were in this regard. Even one of the orphanage teachers would go on to an illustrious career.” [2]

Reverend Jenkins passed away in 1937 and that considerably weakened the spirit of the orphanage. The fire that the house had suffered in 1933 also had left the facilities of the orphanage under complicated conditions. However, the Reverend’s wife, Ella Jenkins, managed to strike a deal with the city of Charleston and secure a new and better location to be the home of the orphans. The band remained active up until the 1980s, when it had to be shut down due to financial and logistical difficulties.

Renamed Daniel Joseph Jenkins Institute for Children, the institute is located in North Charleston and works as a non-profit organization governed by a board of directors and an advisory board. Their mission remains the same: “To promote and support the social and economic well being of children, families, and individuals to enable them to become productive and self-sufficient in their communities.” [6]

While in the past the orphanage received children from both sexes, nowadays it serves as a refuge for girls between the ages of 11 and 21 supervised by a staff of ten professionals, including care specialists and counselors. The institute receives support from local churches and mentoring organizations and, in addition to state funds, the institute is sustained through private donations and grants. They also hope to bring in additional funding by transforming the location into a stop for historical tours by creating a museum to tell the story of the orphanage and the band that helped save the life of so many African American children throughout the years.

One thing is for sure, the impact that one man made in so many people’s lives (not to mention Jazz history) is remarkable.

“Nonetheless, before his death in 1937, Reverend Jenkins could look back on a lifetime of good works that had literally saved or improved the lives of thousands of children – nearly all of whom went on to live productive, self-sufficient, and often famously successful lives. In fact, Jenkins boasted to Time magazine in 1935 that of the thousands of children who had passed through the orphanage since 1891, fewer than 10 had ever ended up in prison – a fairly remarkable statistic given the dire circumstances into which most of his charges were born.” [4]

References

Online articles

[1] The Cradle of JAZZ – Reverend Daniel Jenkins and his orphanage band, Jenkins Institute (http://jenkinsinstitute.org/index.php/our-history)

[2] Jenkins Orphanage Band, Charleston, South Carolina, Symposia (https://www.sc.edu/orphanfilm/orphanage/symposia/scholarship/hubbert/jenkins-orphanage.html)

[3] Jenkins Orphanage and Jenkins Orphanage Band, 20 Franklin Street, College of Charleston (https://www.discovering.cofc.edu/items/show/25)

[4] Jenkins Orphanage Band – Charleston, South Carolina, Sciway (https://www.sciway.net/south-carolina/jenkins-orphanage.html)

[6] Jenkins Orphanage, Sc Picture Project (https://www.scpictureproject.org/charleston-county/jenkins-orphanage.html)

Jenkins Orphanage Band Gave African American Boys Another Chance At Life, Back Then (https://blackthen.com/jenkins-orphanage-band-gave-african-american-boys-another-chance-at-life/ )

The Band, Jenkins Institute (http://jenkinsinstitute.org/index.php/the-music)

The Gullah Geechie, Gullah Geechie Cultural Heritage Corridor Commision (https://gullahgeecheecorridor.org/thegullahgeechee/)

The Gullah: Rice, Slavery, and the Sierra Leone-American Connection, Yale University (https://glc.yale.edu/gullah-rice-slavery-and-sierra-leone-american-connection)

Books

[5] The Wicked Waltz and Other Scandalous Dances, Mark Knowles, 2009

Frankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop, Frankie Manning and Cynthia R. Millman, 2007

Black Dance in the United States from 1916 to 1970, Emery, Lynne Fauley, 1972

A Gullah Guide to Charleston: Walking Through Black History, Alphonso Brown, 2008

Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance, Jacqui Malone, 1996