If you read the subtitle of this part and are thinking, “I’m not a teacher or competitor, so this one isn’t for me!” Please sit, and enjoy this read with the others, I promise it will be worth your time.

“Just don’t rock step” my teacher said as a slower song came on. It was a few weeks into classes and I’d been too afraid to social dance with anyone. We’d had one nice dance earlier and I was confused and intimidated. How do you dance without a rock step? I wondered.

He pulled me close and we had a dance that struck me so hard that it was the beginning of my dance obsession. I went home and tried to find the name of this strange dance. The swing dance without a rockstep. I found a video of my teacher and a woman dancing. I watched it on loop, Blues dancing.

Hours passed, my eyes burning, staring at YouTube on a friend’s couch. Eventually, I stumbled upon a video from an event, called BluesShout.

The video was of a deep voiced, well dressed Black man. He was sitting and speaking to the camera about this dance. It was then that he casually mentioned that not only was Blues, but also Lindy Hop/swing a black dance. I paused the video and sat stunned. Something had been bothering me that I couldn’t quite put my finger on for weeks. The music felt familiar sometimes. In between the Muse and Kesha, I’d find myself singing along to songs and my partners in classes would ask if I had been dancing for a while. But, I didn’t know why. It was just with some partners, to some songs… it felt right.

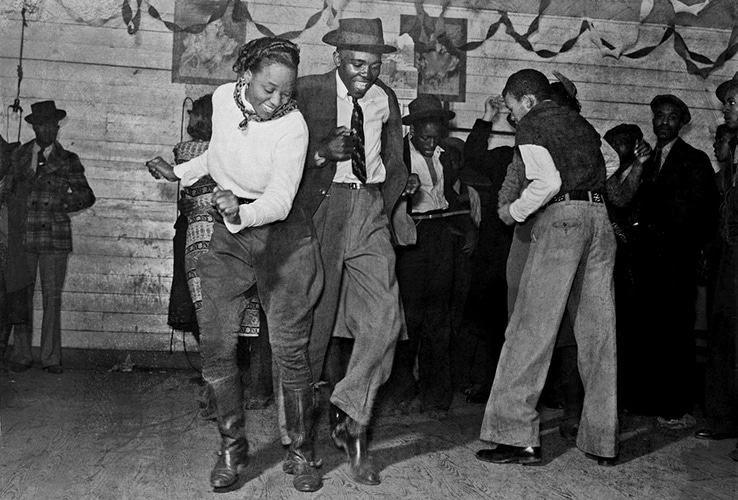

When he mentioned these were Black dances, I realised why. A flood of memories came back to me of spending time with my grandfather. Swing and blues playing throughout the house, singing in the car, and for a short while, me dancing on his feet in the living room.– One of the last times I’d danced before taking these classes –But, I was confused, if these dances were Black, why were there so many videos of white folks? Why did some dancers feel like returning home, and others… not so much? Why did these dances look and feel so at odds with how I wanted to move? Why did the videos I was shown of Hellzapoppin’– after mentioning not being aware that these dances were Black –just seem right, but the very classes I was in, I struggled with getting a feel of.

Image taken from Dirt Cheap Blues

It was these questions and more that nagged at me in my first few years of dancing. When we talk about race in dance communities, I think this is something that often goes overlooked. Over time, I found myself gravitating towards certain instructors, certain events, and particular competition videos. I had videos I’d show my Black friends, openly suggesting they watch *these*. When asked why not the others, I struggled to find the words. Only to show them, and they would also furrow their brow, and chuckle saying something along the lines of “it’s the same… but nah.”

Those teaching these dances, judging and competing in the competitions, and sharing certain videos shape the way that people dance. It changes who we view as excelling in the dance and who fits the idea of the “high level” or “rockstar” dancer.

The problem is, I found myself at odds with majority of the community in terms of what it means to excel at the dance. I thought is was just overly picky until I talked to other Black dancers and realised many of us agreed. I noticed that even though to me it was the Black stylizations that made the most sense, it wasn’t us being held up as #goals.

One thing I regularly say, in courses or discussions about cross-cultural spaces,

is that someone has to be mildly uncomfortable. The question is, as a guest, is it you? If it’s not, that space’s values and the culture has been shifted to be comfortable for you.

Taking classes in Lindy Hop– and competing or dancing with those who take classes –is one of the places this can be particularly clear. As a dance, in many ways Lindy Hop has stagnated. The “wild” edges have been polished, the steps formulated, the romanticised values overexaggerated, the “right” and “wrong” established into a form that is only a shell of what could be. People use Frankie’s voice to drown out any dissenct, to limited dance roles, squash queer representation, and generally try to take the space and values back to the 50s or as the Neo swingers said a “recreation” of it. They wanted to celebrate “America” blindly not realising that 50s America was just a white washed version of the Black 20s and 30s.

Non American dancers have also contributed to this unwittingly. Check out this clip from a interview from the 80s. What I found important here was the cuts between a dancer, Warren Haynes if I heard correctly and Norma; they were directly in conflict in terms of their goals, expectations and focus. He wants counts, he wants to do it “right” and Norma is clearly telling him he’s focused on the wrong things. She says to watch and learn from Frankie for his **vibe** and his **musicality** and to not worry so much about counts. Which focus is in the community today?

See, classes with cross cultural communication are complex things. For example, going to a restaurant of a culture different from where you live. Mostly you have one of two experiences. You enter the space and everything feels unfamiliar, you may not know all the foods, cooking methods and some standard practices are foreign to you. You might order something standard on the menu and struggle to eat it because it’s not catered to your tastes and preferences. Yet watch members of that community dig right in.

The other option is that you go to a place that is catered to your tastes and comfort. Here, it’s common to have American Chinese and Traditional Chinese restaurants for example. They carry very different foods and experiences. Moreover, it’s important to know the difference. There is nothing wrong with liking either but they aren’t the same.

Image from Medium

Most often these are the options when engaging in cross cultural communication. There is one other option though, to have a teacher who is good, and willing, to help you. With this person they are able to get you up to speed much faster and you are able to have a much more enjoyable, deep, and rich experience. Not every teacher can offer this and these days majority of the teachers in swing don’t.

When teachers don’t know the culture well enough to teach it and translate the little nuances in a way the student understands, they can only teach– a let’s say –non-traditional version.

One may learn a lot, it may even be useful but it can’t be the full picture. Add in things like historical power imbalances, and it is unfortunately easy for White members of the community to misrepresent a cultural form, and for that misrepresentation to be seen as “real” and “right”.

In time though, this can create problems. In the case of Lindy Hop, an easy place to see this is in how a class is structured. Are there counts or does the instructor use another way to denote timing? Are movements done to set count patterns or are you encouraged to explore how these things fit into the greater dance? No matter if it’s from Frankie’s teaching (as a performer having strict counts is much more important) or from white culture, which values codification of the arts, doesn’t matter. It simply isn’t traditionally how many Black people teach, or even think about music.

This creates two problems. Firstly, this narrows the timing and expression limiting what kinds of expression seem viable to the average dancer. Also it means that for future hirings the ability to count is expected. To be unable to may remove you from the pool of “qualified” teachers, despite being able to denote time in other ways.

This creates a dual cycle of the dance feeling increasingly foreign to Black dancers AND a devaluation of their styles, knowledge and expertise. So if a Black dancer is unable/unwilling to code switch into something that both feels abnormal, and makes the dance make less sense, they get caught in a whirlpool of problems. Typically until it feels uncomfortable enough for them to leave, get angry and speak out, or stay only feeling able to truly dance like themselves with other Black people.

It’s something I hear often from white dancers that Black dancers (or those from environments that forced them to learn about our culture, ie BBoys, hip hop) dance different. It’s not magic, a major part of it is that we are using tools and values from our culture to inform how we dance.

Counts aren’t the only thing of course. There is a long list of these little things that snowball into bigger and bigger issues. These things range from small shifts, what is valued or emphasised, all the way to what mastery looks like. It changes what bands get hired and how they are expected to play, along with partnering, social power, social norms around dress and more.

All you need to do is look at….

Competition is a great place to see where the scene is going and what is valued. When looking at it with a critical eye, it becomes apparent that there is a lack of the original culture’s values present.

Let’s look at what the community calls a jam circle. When I was a kid it was called just dancing. Randomly between bouts of double dutch, a song would come on, and someone would start dancing. If the other kids liked what they were doing, we’d shout and holler to encourage them to keep going. Screaming and shouting erupted as we gathered ‘round, clapping and generally getting into it. Depending on the group, when the dancer was getting worn out they’d either drag someone else to share the spotlight or another kid would challenge them for the spotlight.

If it was collaborative together they would raise the difficulty, bouncing ideas off one another playfully until one dropped out laughing only for the next person to be brought in. If it had a competitive edge, the goal was to show not only that you’d been working hard on your own dancing, but to elevate and innovate. You witnessed your partner’s growth and showed off your own. You teased and poked fun at them, their style and pointed out their weak points while demoing your new ideas. With two evenly matched folks the group would rise to the highest of euphoria as they met wits and physical prowess. Only for the song to end and laughter and joy to erupt. If there was a good thing going, it would continue.

Image Taken from Paris Jazz Roots Festival

Imagine my surprise to, as an adult, find myself surrounded by white folks and it seems like the same thing is happening! But like getting a oatmeal raisin cookie when you were expecting chocolate chip, I was only to be confused and disappointed. This wasn’t that. People clapped on one and three. No one sang out. No one cheered beyond the occasional woo at the “fancy step”. The crowd stool still or worse, sat down! Dancers didn’t seem to be interacting with each other and were dancing in a bubble of their own. More performance than collaboration. There were rules of how and when to enter. It was assumed only the best could go in. Everything else stopped and many resented it as if it was elitist. In time I learned it wasn’t random, when it felt right, it wasn’t for celebrating someone’s hard work or new movements but was almost always staged. There were “jam songs”, there was a tempo expectation that made it hard for less experienced dancers to participate, and no one encouraged them to, and at the end of the night there was always a jam. Even if it didn’t fit.

Black folks treat competition differently than white folks, in many ways. What mastery looks like is different as well as expectations around behaviour. Most importantly what things we believe are worth celebrating and highlighting doesn’t match white culture. Things like style are highly individualised, both in clothing and in artistry. Dancing to the music is more important than the physical steps. Yet one look at a lindy hop competition and you see a very different experience.

It’s formal. Dancers often perform in a bubble highlighting speed and specific movements over creativity. Everyone dresses pretty much the same and much of the timings are so formulaic, it’s boring to watch. The crowd sits quietly politely clapping at all the right parts. It feels like a sterilised version. But, anyone who is trying to become a figure in the community knows that competition is the easiest and fastest way to gain clout. We know that the way to win is to play the game, and to do what is expected with the best reputation with the powerful people. So the scene bottlenecks into a uniform style, with a set of counts and expectations. No longer is the competition just about who the best dancer is, but who can adhere best to the idealised vision of what Lindy Hop is, even if it’s not representative of them as a dancer or pushing the art form forward.

It’s not about pushing the art forward as it is in Black spaces, which is why dances so often change until they create a new dance to new music. Instead, it’s about who can mimic the idealised version of lindy hop that not only never existed but has stifled all expression, variation, and individualism.

These differences do matter. We have many of the same issues within Blues dancing and a good chunk of the time, as a teacher, I am simply teaching people to let go of white norms for their dancing to improve. Once they are able to shift the norms that dictate their dancing, suddenly things that have troubled them are easier. Parts of the dance make more sense. Why? Because as minor as many of these things seem, they are intrinsic to the art form. Cultural context matters in art. A lot.

There are unspoken rules and ideas that inform the dance and make it what it is. Without them, although it looks similar, it won’t feel right. It won’t be right. Problems that didn’t exist in the original version will crop up. At the beginning, I mentioned that it’s important to read this even if you aren’t a teacher or competitor, and this is why. This isn’t just about “the top” but your experience too. These areas shape your dance life, whether you want them to or not.

Audience throws their shoes at a dancer as a sign of appreciation. Photo taken from ILHC.

Teaching sends values to beginners and sticks with them, and competition reinforces them at the top. It dictates the people you dance with, the classes you have access to, and forms lots of structures that make the scene what it is. You could have a richer relationship to Lindy Hop, swing and the music. This art form can be more expressive. Competition can be more interesting. Community could be more prevalent and diversity could flourish more. Not just racially, but different body types, abilities, stylings, sexualities, and more. We could breathe the life back into the dance, reconnect it to its roots and develop it into a form that actually functions like the Black Lindy Hop scenes and the dances that came out of it back in the 40s.

Next up in this series is all about the structures that bind us, and how we participate in keeping this dance so painfully white…