In the last articles, we explored the history and the white blindness that helped shape the scene’s values, but I think it’s important to look at a specific and important figure…

Frankie signing copies of his autobiography. Photo form Flickr

When I watched the Hellzapoppin’ video as a young dancer I recall being mostly focused on trying to figure out why their dancing looked so different than what I saw around me and… a discomfort with the costumes. It was then that I started hearing the talk about Frankie. People talked about him as though he was a magical figure. It was as if your closeness to Frankie was a status symbol.

“I was at Frankie 100!”

“I took a class from Frankie!”

“I attended dances with Frankie!”

“I talked to Frankie!”

I was confused as to why this guy was the one being so highly upheld. To my eyes, he wasn’t on a whole other level than the other dancers in the video, and honestly, he wasn’t even my favourite. Having started a few years after his death, I could only learn of him through the stories, and the stories made me a bit uncomfortable.

There are two tropes for Black people that I was warily starting to notice and a general vibe I didn’t notice until much later. The magical negro, and Uncle Tom trope. I can feel the discomfort and or anger from most readers, from here, but hear me out. More about the Magical Negro troupe a bit later, but Uncle Tom is a lot of things. It’s a derogatory name, a character, and a trope with many different ways of using it. I am not saying Frankie Manning was an Uncle Tom, I wouldn’t know– I started after his passing remember –but how we talk about him follows both of these tropes.

The tokenism of Frankie has overshadowed all other Black dancers to the point that other famous dancers, and his teammates, are significantly lesser-known. Even today, many Black dancers have discussions about feeling stuck beneath his shadow and compared to the idealized vision of him. These tropes often directly conflict with what Black dancers (including other elders) are/were saying and are used as a way to minimize the experiences of many.

When this comes out, I’ll have been dancing for almost a decade, but if you asked me where Frankie was from, his favourite colour, and what he did outside of dance, I couldn’t tell you. I intentionally didn’t read this autobiography, while writing this series.

Why?

I wanted to highlight other voices, experiences, and sources on Lindy Hop. The fact that I’ve been a part of the scene so long, conducted interviews, and read multiple books and articles on Lindy Hop, and still know next to nothing about the man, as just a man, really saddens me.

Does no one else find it distressing that only one dancer is celebrated – so much more than the rest – in Hellzapoppin and that the dancers that came before him are rarely discussed? Or that the ones who continued their dancing careers, without a hiatus, aren’t as highly regarded? Instead, we have the stories about saving Frankie from the post office. How joyous he was and unchallenging he was. How his dancing was “special”.

I never hear anything about him being unhappy but instead how so many memories of him are twisted to fit any narrative as long as it maintains the status quo. And finally how that giving nature has allowed for non-Black people to stake claim of the dance and do with it what they will.

– Leading = Men, and Ladies = follows

– There was no same sex couples dancing together

– You can’t dance to Bebop

– Lindy Hop is only about fun

– Everyone owns Lindy Hop

– No one owns Lindy Hop

– Lindy Hop died

– We “white folks” saved Lindy Hop

– There is no racism in the Lindy scene

– Blues dancing doesn’t exist

– Certain qualities of Frankie’s dancing is the only way to do Lindy Hop

– There is no wrong way to do Lindy Hop

– No one cared what race you were

One thing I’ve noticed about non-Black people is that they never seem to consider the context. Frankie was born in 1914. Although Jim Crow was predominantly in the South, it pulled from many ideas from the North, and these laws were enacted over 30 years before Frankie was even born. This is before the music industry even started selling “race records” because we weren’t viewed as a population worth recording or selling to. We are only slightly (~ two years) more distant from the end of the civil-rights era as his birth was from the start of the Civil War.

Consider how much progress we have, and haven’t made since the Civil Rights Era. I still see the effects of my mother being raised by folks who lived before and through that era of us getting rights in myself. When I interact with white Americans of a certain age, I start to follow engrained rules even though I grew up in an era of “post racial equality”. It’s foolish to not look at how the time Frankie was raised in would affect how he interacted with white people. What he would and wouldn’t say, and how he’d react to suddenly being celebrated for something he did over 30 years prior, as a child and young man.

There is a great danger in looking at the words of Black people in the past, during cross-cultural contexts, in isolation. Most of us do not, and can not safely, act the same as we would naturally in white spaces. To get along in white spaces many of us have to hide, code switch, and strip away parts of ourselves to maintain a very precarious position, or be left behind. The higher up one gets, the more being able to play a role is crucial to being able to survive.

It’s only now that Black people in powerful positions are more common, that we are able to speak out with fewer consequences. My mother had death threats in the 90s for speaking out against unfair hiring practices in a small town for an entry-level position. This isn’t so far in the past as we like to act. To ignore the reality of what it is like to be Black and in power is seeing the past through rose-tinted glasses.

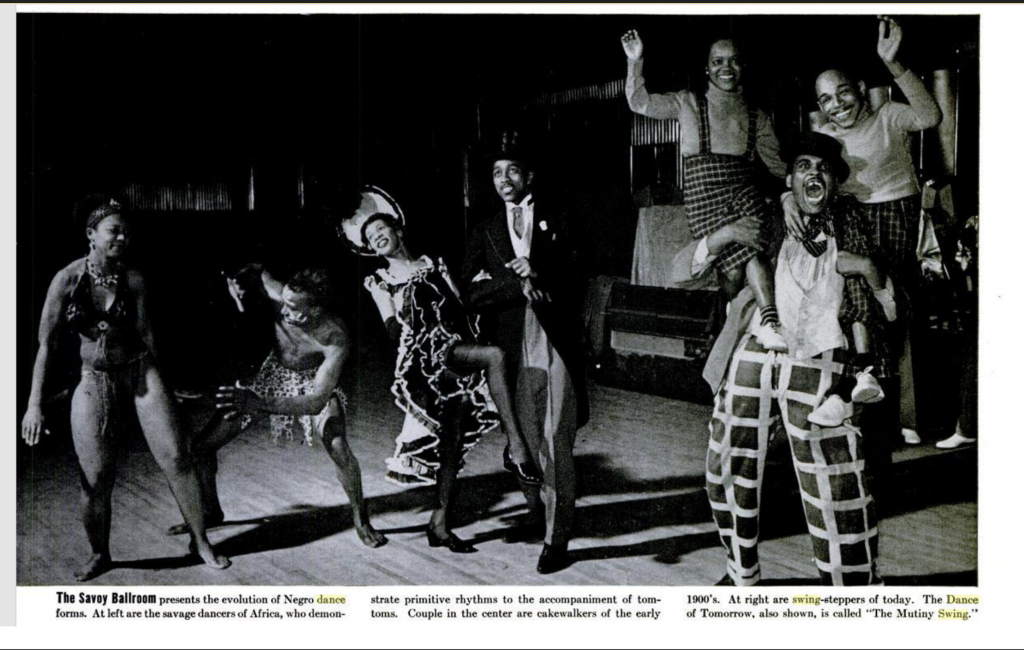

Let’s talk a little bit about the Savoy Ballroom without the romanticized air. The Savoy was unique for a few reasons. A white man and a Jewish man owned the place. They instated rules and expectations around what was allowed in the place.

Many of these rules played into respectability politics. The Savoy did eventually get alcohol at its venue. (Note: Frankie was 19 and legally too young to drink when he started as it changed to 21 after Prohibition). Clubs at the time either excluded Black people, and were more often raided and assessed, or simply had excessive costs because the owners were Black.

That meant that most Black-owned ballrooms were typically owned by the Black Upper Class. They tried to distance themselves from the Blacks coming in from the South and leaned into the respectability politics of the time, truly thinking that if they bettered themselves they would eventually be accepted. Many were eventually closed down because of excessive fines.

If you weren’t involved in that part of the Black population, as most of us weren’t, there were jook joints and rent parties. I think sometimes swing dancers forget that rent parties happened alongside the Savoy being open. These parties were crowded, filled with people eating and drinking alcohol which was illegal to do until 1933. People smoked and hit on each other. These venues were where many performers got their chops, dances were continued (ie blues and many others) and an important co-mingling of Black southern and northern culture occurred. These parties were critical for many Black adults at the time, both financially but also as a way to gather that wasn’t as heavily policed and taxed.

The Savoy Ballroom was not owned by Black people and so had a very different set of values and impact. They were able to have opulence because of the advantage of having a white owner. Don’t misunderstand. This wasn’t (just) out of some goodness of heart. “it… grosses $275,000 annually, has 150 people on its payroll, pays its two orchestras $1,200 a week, its Black manager $100 a week, and provides over $100,000 a year for its white owners.” They employed “dance ambassadors” a history which is important and you should read — Dr. Christi Jay Wells’ book, “Between Beats: The Jazz Tradition and Black Vernacular Dance”— to learn more about it.

People like to focus on the fact that the Savoy was interracial. Not only was it not the only place to be so, but interracial dancing was still frowned upon. Generally, the venue was 80% Black and only 15% white. Keep in mind that not every night had those percentages and only a few more percentage-wise than the Black population of the US. We know how easy it is to avoid 13-15 percentage of a population. I’d suggest that this was only even possible because of the respectability politics and the Savoy not being owned by Black people. White people didn’t generally go to the other Black venues or rent parties because they had other options. The important thing to realize is that what allowed the Savoy to do the cutting edge and taboo things it did, was dependent on it having a white owner. White people could have had a venue like this but chose not to, while Blacks never had the tools and privileges to create it for themselves.

Many Black bands got respected and paid in this venue which other venues didn’t allow. What made Savoy special was that they treated Black people (and immigrants for that matter) as people, as long as we adhered to their rules, and in return got a center of cultural and artistic development. But to ignore why this was such an unusual place, and all the Black spaces around it, only limits what we know about the time, the people that lived during it, and how it impacts us today.

This is the environment that Frankie entered when he came in as a dancer. Too young to drink, probably too young to attend very many rent parties, and likely too poor to attend the upper-class events, he joined a community of dancing to emerging music. Norma says in an interview that at the time it was just seen as “just dancing” and remarks on her surprise that it has become what it has today. Frankie, a kid, did what kids do in our culture. He, and his friends built upon the foundation established by our elders to elevate the arts to a new level.

So it was in this environment that he grew into a dancer, joined Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers, and eventually left swing. The group was both a boon and had a cost of being mistreated by Whitey. These young folks joined and were paraded and celebrated around the world despite being young poor kids from Harlem, of course, they stayed. But they still faced great adversity while doing so when in the states. Because outside of their ability to perform, they were just Negros (I am using this term specifically here). They were treated as such and one only needs to look at the costumes of Hellzapoppin’ to see how they were treated. Like most Black performers at the time, I can only assume there are stories of racism, prejudice, hate, and police harassment that also are a part of their story.

Meanwhile, White Culture was looking to dilute and control the “wild” dance til it could be taught to the white kids who were excited about it. White bands started picking up the music and codifying it. They pushed out the Black bands as they learned to play, and new venues for white dancers sprang up. Does no one else find it interesting for a nationwide craze, that one of the biggest venues, the one that is said to have created it, stayed at only 15% white? By the time Whitey’s disbanded in 1942, the narrative around Swing had totally shifted. Lindy Hop was “America’s dance”, the most celebrated swing dancers, bands, and records were all white.

Meanwhile, Black artists were struggling to get work. There had already been a movement towards a different style of music in the early 40s, one which by the end of WWII had gained popularity in Black spaces: Bebop. While the war happened, the youth too young to be drafted continued to do what we always do, and build off the foundation of our elders. Bebop, the musical equivalent of a middle finger to white America, flourished in Black communities and venues. Tiny spaces were where musicians got together to push themselves and although they didn’t cater to dancers’ sensibilities, the myth that no dancing was done is incorrect. White folks couldn’t play or dance to this music, but some Black kids did. Unable to swing out, the dance shifted to fit the music and the space.

Once Frankie came back from the war in his early 30s the dance had moved on. Unlike many of his elders and comrades he didn’t and/or was unable to, create a career as an artist. See, he chose not to learn Bebop and therefore didn’t go down the other path of dances (see Part 2 if you missed this history). At the same time though, he didn’t go down the path that some of his peers did, expanding into other styles and performances. He found his way into the post office and didn’t leave.

Why did I go into all this history and context? I think it’s important to look at it in order to be able to see what shaped Frankie into the person that was “found” in the 80s. By this time, Leon James had died rather young. Al Minns was found before Frankie, and yet, he too died before the “revival” really took place. They, and many others, had continued dancing. By the late 80s, the Black community was being overwhelmed by AIDS and crack cocaine. At the time there was growing dissent in the Black community, being artistically represented by Hip Hop Culture. Although we don’t, on a whole, romanticize the past, one doesn’t need to look too hard to see Swing influences in the dancing that came out of Hip Hop.

Yet it was the Swedish who first became enamoured with the idea of Lindy Hop. People without any knowledge of this history, nor the ability to see Swing in Hip Hop, nor access to the Steppin’ Community, simply found videos and searched down the people in them. At the same time, the aging “punks” of the day – who had started after the traditional trappings of being punk became too mainstream – started to romanticize the past. With that, they started a movement toward finding and celebrating anything that was currently scorned by the public. In a way becoming exactly what punks before them rebelled against. At the same time, Jazz had become a status symbol of the white upper class.

With that, there were many non-Black people fighting over the legacy of swing and jazz, and the circumstances aligned that Frankie was one of the few people to still be alive and an original dancer of the time, with clout. And so Frankie went from 30 years of working in the post office, while many of his peers continued artistic careers throughout their life, to being thrust in front of white eyes both in America and outside the country. Those abroad wanted access to an original dancer and created a movement in America. While mainstream America was in love with the white idealized version of Swing in its youths then realized they could make money from it and needed someone to emulate. While the “Swingers” didn’t put Frankie on a pedestal, they too would eventually, once being a good dancer had social clout tied to it.

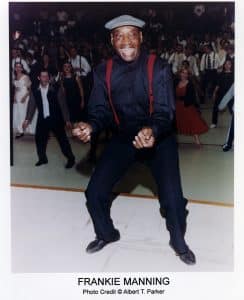

Frankie leading the Shim Sham

Can you imagine in your 60s being able to retire from a dead-end job, and into money and fame?

Even if it might be dependent on being willing to tell people what they wanted to hear and holding your tongue, I assure you most people would do it. Can you imagine actually being paid for what you love to do and for doing the code-switching that normally isn’t appreciated at all?

Now I’m not saying that Frankie lied or didn’t mean what he said, just that we have to consider that his view is ONE of many. Frankie’s viewpoint can’t represent all of the histories of Swing. Besides, what we had access to of him as a public figure, might not have been the full picture. Whereas, those who spoke up more, are less celebrated. The Black women are ignored as nothing more than the “partners” of the greats, not as artists in their own right, and often tell conflicting stories to those of the men. Their discussion of controversial topics got swept under the rug, in favour of the image of the easy-going Black man who was supportive of anything the white dancers did.

Black people have been talking about race in the Lindy Hop Community in various ways since the beginning. We aren’t a monolith. So as much as I don’t agree with everything that was said, we can’t continue to ignore that it happened for a romanticized vision of who Frankie was. It’s disrespectful to him, to us, and to his peers.

Many Black dancers feel smothered under the weight of his legacy and the worship of his words out of context. Our behaviour is judged against his image. He is used against us to invalidate our very real feelings and problems as not a big deal or not real; as if his blackness outweighs ours and his peers because he said unchallenging things. He isn’t Black people today, and we have to remember that. Black folks today have inherited the hard-fought ability to speak out more with fewer consequences. We can say the things that might have got Frankie killed. We can demand the respect that was unheard of and not expected.

When the community puts Frankie on a pedestal, using closeness to him for clout, and using his words to keep today’s Black folk down, because people don’t want to have to actually deal with hard things, it hurts us all. I don’t think that’s the best way to show your love for this man or the dance. When you love something you love the good with the bad. You appreciate the strengths along with the flaws. You love the full picture, not just what you want to see.

Frankie was a man. A man who did some amazing things in his lifetime and brought a lot of joy to people, but not a deity. He was as flawed as the rest of us, and no one person can speak for a movement, nor a people. His dancing was one way of doing it, his views and opinions were just that, and his experiences were one voice in a choir of experiences. Life is best viewed through its harmonies, not a lone soloist.

It’s important to look at Frankie as a man and not just a figure, because he was who so many looked up to and looked at as a teacher. He has to be seen as more than just an image of the values people want to superimpose onto the dance. His legacy shouldn’t dwarf the voices of his peers to the point that knowing anything about them is seen as being well-educated. Frankie’s styling and beliefs shouldn’t smother the expression and experiences of the art form. His perspective shouldn’t invalidate the rest our ours.

Many people over the years either have held onto classes or those taught by Frankie as having a gold star towards their teaching credentials. Instructors quote Frankie, foundations support rising instructors are based on his values, and performances are judged against his. This limited view of Frankie and the history and culture of the dance, along with the dismissal of other Black voices, has directly impacted how Lindy is taught today, and who gets to teach it.

This treatment of the Legacy of Frankie Manning has shaped and limited the culture around Lindy Hop, how and what we teach, what we value in competition, and who we see as worthy of being celebrated. I think that is a problem and right now we have the ability to start looking at this issue and fixing it. Next month we will be talking about it!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tim Collinssays:

Thank you Grey Armstrong