It’s the 1930s, and the night is young. Walking down the streets of Harlem, you can’t miss the block-wide building lit up with a line out the door, The Savoy Ballroom. The Savoy Ballroom, a famous dance hall, was gaining a reputation for having the best bands and dancers. Artists who were on the cutting edge of innovation when it came to the emerging style of swing.

Walking inside, through the glamorous scene, up the stairs lined with mirrors and through the double doors, you’d see a crowded dance floor filled with 3,000-5,000 people. With two bandstands, Savoy hosted many of the names that would later be known to be the biggest names in swing such as; Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, and of course, Chick Webb.

Widely known as one of the few affordable places Black Young adults could dance, they flocked there for a good time. The dance floor, called “The Track”, was filled with Black American dancers, as well as an upwards of 15% white American dancers, which was unheard of at the time. It was also not abnormal to see women dancing with each other, or interracial couples, the Savoy brought in all kinds. The seating around The Track would be filled with Black youths; flirting, kissing, drinking and smoking. Different nights catered to different crowds but everyone was always dressed to impress. It was a social dance after all!

It was here, amongst many other burgeoning dances, that it’s said Lindy Hop was created.

Where does the name Lindy Hop come from?

The story you are most likely to hear is that a dancer named Snowden was asked the name of what he was dancing and saw a paper describing a historic flight and said “the Lindy hop”. As fun and as easily digestible as this story is, scholars remain divided on its validity. There are a few alternative theories that suggest maybe the name’s history is more complex than we typically say. You can read more about this here. Specifically, other sources and scholars around the name are discussed on pages 3-7.

No matter how it got its name, if you wanted to see the most cutting edge dancing, well you’d go to the northeast corner of The Track and find “The Corner”.

This was where the best dancers spent much of their time. In the 20s it was the first generation of dancers like Shorty George, Big Bea and Leroy Jones, but by the mid 30s they were replaced by some younger teen upstarts.

Dancers like; Willa Mae Ricker, Leon James, Norma Miller, Frankie Manning, and many many more, took the dance started by the earlier generation, and made it theirs. Many of the regulars to The Corner would go on to join performance teams and compete in competitions. It was in one of these competitions that Frankie Manning created airsteps, while dancers from Savoy dominated competitions outside of the ballroom.

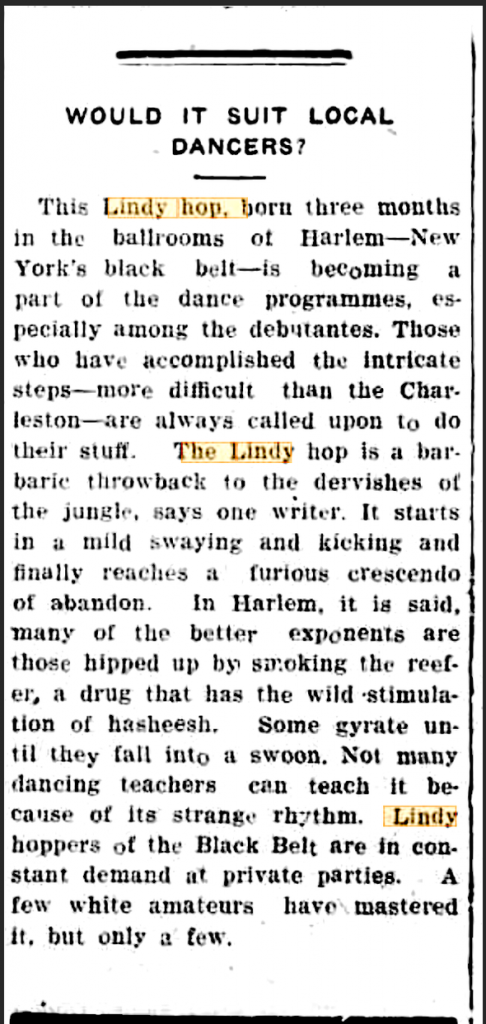

At the time, ironically, the white American dominated dance world wasn’t impressed. Not only that, but they saw the dance as a “wild” and “inappropriate” fad for white dancers, at best. Or impossible at worst.

Of course, it wasn’t, and white youth culture eventually got sucked into the gravity of the swing movement.

With an increasing demand for Lindy Hop classes and dancing opportunities, white businesses started to notice the movement. Record companies started recording Black artists for the first time, creating race records to sell to Black audiences. Meanwhile, they also got Black artists to write music for white bands to record and play. White dance instructors yielded to the demands, and figured if they were going to teach it, they might as well “clean it up”.

With these two shifts, the way the white community talked about swing started to change, along with the music and dance they brought with them. People like Arthur Murray (creator of East Coast Swing) codified and simplified the dance for white palettes.

With those changes, the music and dance really took off. Not only with the white youths of the day, but Lindy Hop became a mainstream phononome. This shift in the people dominating the culture, values, and expectations meant a change in who was getting work as musicians and dancers. By the late 40s, white Americans were saying they had cleaned up the swing dances. Most people described their dancing as “Jitterbug” rather than Lindy Hop. This was not just happening with swing, but jazz as a whole. Now it was an “American” art form, not just a negro one.

Lindy Hop dancers today may hear that Lindy Hop died. Or may hear people describe the resurgence of white interest in the dance in the 90s as a revival. These are myths. The dance didn’t die. So why do you hear that?

The short answer is that it died in the white community. Meanwhile, Black dancers innovated on top of it, into other dances. Many of the Black performers still performed swing and jazz dances, until their deaths. Even today jazz is still a big deal in the Black community and the swing dances are kept alive through its descendant dances like Steppin’ or DC Hand dancing. Even when the Savoy did eventually close, that’s not to say Black people stopped dancing. In Harlem, they never stopped and can be found still hosting dances there today.

But, that wasn’t what people meant by it dying. They meant that it stopped being “a thing” in white circles. Between the Black musicians and dancers shifting to Bebop, white bands were left without inspiration, ballooning the size and cost of bands; because of that and the shifting interests of white youths, it became unsustainable. By the 50s, the new batch of white kids had caught on to R&B and what would become rock and roll, starting a movement of rejecting partner dances for the lure of solo ones like the twist.

But a good thing can’t stay down forever. In the 70s, there was a push by media to go back to the good ol days. Things were changing fast, in America, around race and rights. Many white people wanted to return to when things were “simple and wholesome”. Which equated to the romanticised vision of the 30s and 40s. By the 80s, two different communities started what would create the resurgence of Lindy Hop into the white mainstream consciousness, in the 90s. There was the Neo Swing community and the Lindy Hop dancers.

The Neo swing community, a group of punks who were disillusioned with the scene, broke off and fell in love with the idea of American exceptionalism. Seeing the past as the best America had offered thus far, they sought out anything related to older time periods and began collecting. Bands started putting a ska punk spin on swing music and small groups went to lounges to drink, dance and talk vintage.

Meanwhile, some people had found videos of the old Lindy dancers. They started searching them out to ask them to teach them to dance. It spread far and wide as people in the US and Europe alike became obsessed with the idea of preserving this dance and history. New big bands found old charts and started to play them. Many were so excited they started their own communities.

Swing in the 90s hit its fever pitch with the Gap Khaki Swing commercial.

Sending these lesser-known communities into the limelight as they were flooded with new dancers willing to do anything to learn to look like that. Before long, the two different communities combined instead of having light cross over between them. With that the scene became a worldwide phenomenon.

Today, we can see the effects of this history in how we talk and go about dance in the scene. This history is important because it not only preserves the legacy of the culture that created it, but also allows Black Americans to pass down that heritage. With it we can also have a better understanding of why the current community is the way that it is, look at how history is still affecting us today, and have a deeper understanding of swing music and dances.

Moving forward we are wanting to acknowledge this history more. It’s important to look at how we have inherited some beliefs and assumptions that may not be serving the dance, or us as dancers. We are wanting to be sure we respect the cultural heritage of Lindy Hop, as well as the people, so one day we can have a scene where everyone feels welcome. Hopefully, we will be able to respectfully breathe life, creativity and Black values back into the dance. In doing so, we earn more about ourselves, along the way, as we learn and celebrate the dance we love.